The Dancing Satyr (Satiro danzante) is a bronze statue of a mythological character, raised from the depths of the Sicilian Strait (Canale di Sicilia) between Sicily and Tunisia, which amazed and delighted the world with the newly rediscovered masterpiece of ancient Greek art.

Page Contents

The Gift of the Sea

It became known on the night of March 4, 1998, that the Mediterranean Sea, in the area between the Italian island of Pantelleria, located 100 km (about 62 miles) southwest of Sicily, and the Cape Bon (Capo Bon) peninsula in Tunisia, had presented a generous gift. The fishing boat “Capitan Ciccio” (Capitan Ciccio) led by Francesco Adragna entered the port of Mazara del Vallo with a priceless cargo—a bronze statue of a young man, raised from a depth of 500 meters (1640 feet).

This vital discovery was anticipated, as nearly a year earlier, on March 29, 1997, in the same waters, the same team had retrieved the statue’s left leg, which gave hope for a more “rich catch.” The enthusiastic searchers continued with specialized equipment; a sonar (a device for scanning) was used to thoroughly examine the seabed at depths of 480-500 meters (1575-1640 feet), which could signal the presence of metal objects.

The presumed location of the statue posed a danger to navigation due to underwater rocks and reefs, but the risk was justified—at a site 80 miles northwest of Trapani (Trapani), in the area of the presumed artifact accumulations of a sunken ship, the long-awaited find was discovered.

The Character and the Era

After being raised from the depths of the sea, the Dancing Satyr was transferred to the Istituto Superiore per la Conservazione ed il Restauro in Rome, where it underwent three years of restoration and research.

The appearance of the found bronze statue immediately allowed scientists to effortlessly recognize the mythological creature from the entourage of the Greek god Dionysus – the dancing satyr.

Half-human, half-beast, a forest deity endowed with a cheerful and licentious nature, spends all its time in drunkenness and chasing nymphs. Satyrs had a particular passion for music and dance, which they indulged in after a few sips of wine. Interestingly, according to mythology, it was the satyrs who first prepared the intoxicating beverage from grapevine clusters.

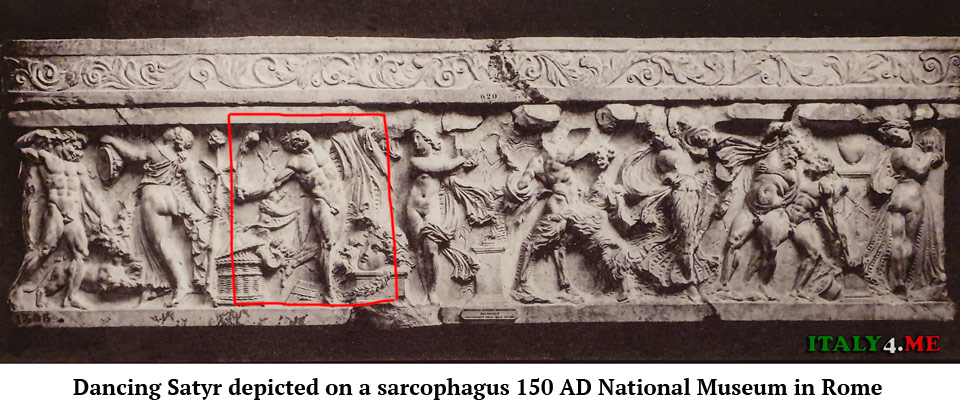

The found statue had all the hallmarks of a fantastical satyr: pointed ears, a hole in the lower back for attaching a tail, a frozen dynamic pose of rapid dance, and expressive facial expressions of a mood intoxicated by wine. For a satyr, one of the distinctive features is an unnaturally tilted head to the side – a sign of inebriation, madness, and ecstasy during dances. This established image of the Satyr is embodied in numerous paintings, bas-reliefs, and sculptures during the height of the cult of the wine-making god, which lasted about five centuries.

While scholars easily and unanimously identified the statue’s character, the time of its creation is debated. It is assumed that the Dancing Satyr is a Greek original sculpture from the early Hellenistic period, i.e., from the second half of the 4th century BC to the 1st century BC.

Unfortunately, there are currently no reliable methods for the identification of ancient objects, so specialists use stylistic-iconographic analysis to put forward their hypotheses and conclusions.

Description of the Find

The bronze statue of the Satyr from Mazara del Vallo is slightly taller than a human, about 8.2 feet (2.5 meters) high, weighs 238 pounds (108 kg), and lacks arms, a right leg, and a tail. However, the eye sclerae, made of alabaster, have been preserved remarkably well.

The thickness of the hollow statue’s walls varies from 0.28 to 0.63 inches (7 to 16 mm), and metallographic analysis revealed the material’s heterogeneity – the alloy contains lead (16-17%), typical for Roman works of the early Hellenistic period.

Details of the statue were welded in various ways, with connecting seams visible on the front of the neck, buttocks, left groin, and at the point of attachment of the right hand.

An internal examination of the statue showed that the craftsman used the “lost wax” casting technique often employed by ancient sculptors. Confirmation of this was obtained during scanning of the torso, which revealed remnants of wax, traces of cleaning, and even fingerprints of the artisan.

The find’s structure appeared very fragile, with numerous cracks, chips, and breaks. Analysis of the material at these sites confirmed that most of the damage dated back to ancient times, not just to the sea’s subsequent mechanical and chemical effects. This fact led to the speculation that the bronze satyr might have been transported along with other scrap intended for smelting.

Restoration

After thoroughly studying the statue using all available modern methods, I discovered that it underwent mechanical and chemical cleaning followed by a series of complex restoration works. Especially for the Dancing Satyr, the aerospace mechanics department of the University of Rome “La Sapienza” designed a sophisticated adjustable support, allowing the statue to be moved and rotated without the risk of damage, even during the shocks of an earthquake (Mazara del Vallo is in a seismic zone). The skillfully conducted restoration allows us to admire the ancient masterpiece in all its glory today.

Watch this informative video on how the Satyr was restored:

The Image and the Dance

The Dancing Satyr is admired for its magnificent body proportions, the incredibly complex frozen motion of the dance, the “alive” wave of hair, and the exciting and sensual facial features with vividly conveyed emotion. Even the absence of some body parts and image elements vividly represents the mythological character. Dionysus’s companion spins on the toes of his right supporting foot while the slightly bent left leg is frozen in the air; the arms are stretched forward by the force of inertia from the rapid spin.

It is assumed that one hand bore a draped leopard skin—an integral attribute of a satyr. In his left hand, he held a kantharos—a ritual wine cup with high handles, and in his right hand, a thyrsus, twined with ivy or grapevine and topped with a pine cone. This decorative element of the staff helped induce the Satyr into a trance, which he did not break his gaze from during the dance.

Ritual dances of the dervishes in Cappadocia, Turkey, are known, during which they, uniformly spinning around a single axis, fall into a similar trance.

The dance of the Satyr is somewhat different, featuring a complex and dynamic pattern, more akin to an exuberant tarantella or a whirlwind. The ascetic dance of the dervish is driven by a religious impulse. In contrast, the Satyr, having emptied his wine cup, whirls carefree in the merry carousel of his companions, hopping and leaping with childlike spontaneity, mimicking animals and birds. He has leaped upwards and is literally frozen on tiptoes, trembling with his whole body—this moment is captured in bronze by the talented sculptor.

Similar ancient images to the Dancing Satyr from Mazara del Vallo exist. The statue of his mythological companion, the Maenad (Bacchante) by Scopas, dating to 355 BC, a copy of which is exhibited in Dresden, repeats the same body angle, the sweep of the arms, and the position of the head.

A small bronze figure from Pompeii, “Dancing Faun” (2nd century BC), displayed in Naples in the National Archaeological Museum (Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli), is also a character from Dionysus’s merry company, with characteristic features and movements.

Scenes with images of satyrs and maenads dancing in a trance can be seen on ancient bas-reliefs in the museums of Boston and Prado, as well as on numerous ancient Greek vessels and in jewelry, which are exhibits of other thematic exhibitions.

The Dancing Satyr can also be seen on a sarcophagus found at the Villa Salaria, dated 150 BC, and in the National Museum of Rome (Museo Nazionale Romano).

Where Was It Being Transported?

It’s always fascinating to know where ancient ships were transporting valuable cargoes from and to.

A theory considered was that the Dancing Satyr raised from the sea bed might have been mounted on the stern of the sunken ship, but the fixture through the hole in the left heel is unlikely to have withstood the ship’s rocking.

Most likely, the statue was part of the transported cargo. The trade of art objects was widespread in the early Hellenistic period; especially valued were the works of Greek masters, which were greatly admired by the inhabitants of Magna Graecia, Macedonia, and many regions of Asia. In Athens, there was even an informal school for mastering the art of copying works by famous authors.

With the expansion of the Roman Empire in the Mediterranean, the plundering of art and architecture became widespread. In Roman times, Sicily became a center for the outflow of classical masterpieces, subjected to looting and export, including by sea.

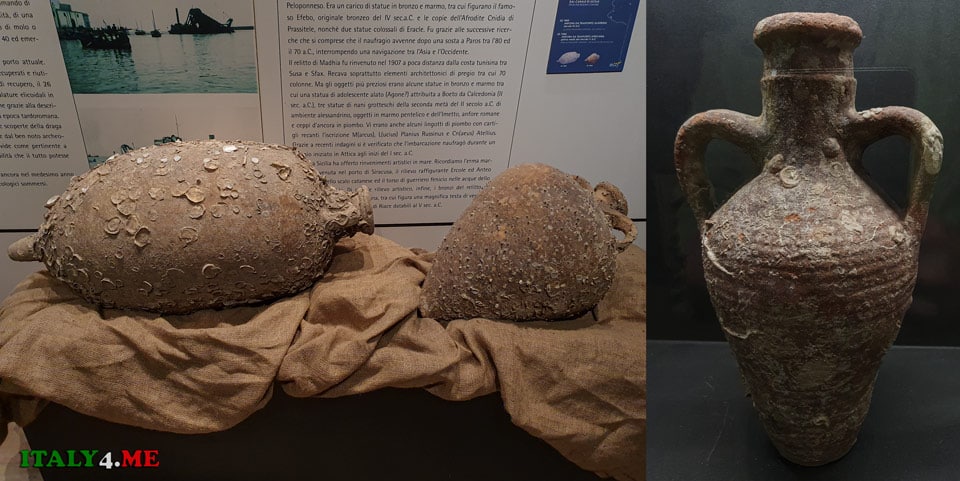

A collection of amphoras is presented in the Satyr Museum.

The journey of the Satyr will remain a mystery, but like many works by talented Greek masters, it was attempted to be taken from the island and sold in another country, recognizing its high artistic value.

Art historians and historians have studied the bronze satyr, suggesting that it may be one of the characters in a compositional group of Dionysus’s companions, connected by the sculptor’s design into a volumetric picture of a ritual dance at the height of a festival of pleasures.

Perhaps the sea, holding treasures of past epochs, will delight the world with new finds of mythological characters as incredibly beautiful and astonishing as the Dancing Satyr from Mazara del Vallo.

Address and Museum Hours

Given the great value and uniqueness of the artifact raised from the seabed, the “Dancing Satyr” Museum (Museo del Satiro Tanzanite) was established in 2005 in the former Church of Sant’Egidio (Chiesa di Sant’Egidio) in Mazara del Vallo. Here, visitors can admire the bronze statue and other interesting archaeological finds discovered in the waters off the city’s coast.

The museum features a film about the Dancing Satyr’s discovery history and interesting information about its restoration works.

- Museum address: Chiesa di Sant’Egidio, Piazza Plebiscito, Province: Trapani, Municipality: Mazara del Vallo

- Hours of operation: daily, including holidays: from 9:00 AM to 7:45 PM

- General admission is 6 euros, reduced ticket – 3 euros

If you’re arriving by car, I recommend leaving your vehicle at the free parking along the Lungo Mare Mazzini promenade. Enter the pizzeria Del Marinaio into your navigation system.

It’s just a few minutes’ walk from the promenade to Piazza Plebiscito. Before your trip, consider exploring my author’s 10-day itinerary in Sicily.

After visiting the museum, I recommend stopping by the Jesuit College (Collegio dei Gesuiti), which is opposite, where you’ll see a beautiful door.

The college has a gorgeous courtyard, and exhibitions are held in the rooms, with free admission.

I hope I’ve inspired you to travel and explore the western part of Sicily. If you’ve already visited Mazara and seen the Satyr, please share your review in the comments.

Italy for me From Italy with love

Italy for me From Italy with love