Roman gods and goddesses represent one of the most vivid and significant chapters in the history of Ancient Rome. The divine realm existed alongside the world of humans, shaping their worldview, traditions, and culture. Divine powers inspired the Romans to build grand temples, create magnificent works of art, wage victorious wars, and achieve great conquests.

Page Contents

Archaic Roman Religion

The archaic religion of the Romans was a direct inheritance from the ancient culture of the Indo-Europeans, who migrated to the Apennine Peninsula in the 15th century BC, bringing with them pagan traditions and cults.

Initially, the gods were not personified, and the tribes inhabiting Central Italy during the prehistoric period worshiped animistic supernatural forces. By conducting various rites, people believed that sacred spirits could influence all objects and phenomena of nature and impact their fate.

Initially, the gods were not personified, and the tribes inhabiting Central Italy during the prehistoric period worshiped animistic supernatural forces. By conducting various rites, people believed that sacred spirits could influence all objects and phenomena of nature and impact their fate.

The religion of the Italian people initially lacked a mythology narrating the creation of the world and the deeds of deities. It formed over several centuries under the influence of Etruscan, Greek, and Near Eastern civilizations, which introduced beautiful stories about gods and heroes’ exploits to the Roman world.

Roman divine entities gradually acquired human traits as they developed their legends and formed a complex pantheon of gods.

The Regal Period

The Regal Period of Ancient Rome (8th-6th centuries BC) is characterized by the worship of “local” deities, i.e., those not borrowed from other peoples’ religions. Literary works by ancient authors have preserved legends about their origins, purposes, and roles in the lives of the Romans. During this time, major religious cults were formed, and the order of numerous ritual ceremonies was established.

This dynamic interplay between religion and society underscores how deeply intertwined the divine was with every aspect of Roman life, from governance and warfare to art and daily rituals, highlighting the central role religion played in shaping the identity and achievements of Ancient Rome.

The Kings of Rome and the Gods

According to ancient narratives, the early Roman gods once lived in the territory of Lazio (Lazio) as humans or beast-like beings. They were distinguished by their abilities and deeds, so after death, they gained the local population’s awe and the power of patrons.

The early history of Rome was full of legends about the founding of cities. Among its heroes are the first rulers, the seven kings:

- Romulus

- Numa Pompilius

- Tullus Hostilius

- Ancus Marcius

- Tarquinius Priscus

- Servius Tullius

- Lucius Tarquinius Superbus.

They are not so much historical figures as they are semi-mythical characters whom the Romans worshiped as gods after their death. Golden statues of the seven kings were placed in the Roman Forum (Foro Romano) and stood there until 410 AD when they were melted down into ingots to provide a ransom for the Visigoth king Alaric.

The divine nature of the kings of Rome is mentioned in various legends.

For example, the ancestor of Romulus and Remus was considered the hero of Greek mythology, Aeneas, son of Venus, who fled to Italy from the destroyed Troy. Romulus himself, supposedly born from the union of the vestal Rhea Silvia and Mars, became identified with the god Quirinus after his sudden disappearance.

According to one legend, Servius Tullius, who built the famous Servian Wall (Mura Serviane) to protect Rome, was born of the god Vulcan, who was captivated by the beauty of his mother, Ocresia, from the Tullius family.

The second king of Rome, Numa Pompilius, interacted with the gods daily. He became famous for creating a written code of laws, Commentarius Numae, which established ceremonies and sacred rites for different religious orders. It is believed that Jupiter negotiated with Numa Pompilius to develop the principles of Roman religion.

Interesting fact: in the Borghese Gallery, there is a sculpture of Aeneas, Anchises, and Ascanius, telling the story of Aeneas’s escape from Troy burning in flames.

The Archaic Triad

The list of ancient Roman deities included more than two hundred names. Three of them, the most important, stood out as the so-called Archaic Triad. It consisted of Jupiter, Mars, and Quirinus.

This triad of gods corresponded to the sacred formula of the most ancient religions. The heavenly king held the dominant role in this structure, endowed with supreme authority (Jupiter). Following him was the deity of martial prowess (Mars). The third in the triad was the god representing earthly human values and pleasures (Quirinus).

What gods formed the alliance of the main supreme forces like?

Jupiter

Jupiter – the deity of the sky and light, king of all gods, maintained his leading role in the Roman pantheon until Christianity became the main religion of the Empire.

Regarded as the principal patron of Rome, he had many other functions: Jupiter Tonans (Iuppiter Tonans) – sending thunder and rain, Jupiter Victor (Iuppiter Victor) – granting victory, Jupiter Terminus (Iuppiter Terminus) — the guardian of boundaries, Jupiter Feretrius (Iuppiter Feretrius) – the god of war, etc.

In the 6th century BC, the most important and grand religious building of Ancient Rome, the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus (Tempio di Giove Ottimo Massimo), also known as the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus, was built on the Capitoline Hill.

Today, the remains of the temple can be seen when visiting the Capitoline Museums.

Mars

Mars is a god with Italian and Etruscan roots, second in importance only to Jupiter.

In archaic religion, he was a god of rain, thunder, and fertility, then revered as the progenitor and guardian of Rome, and later became the god of war and valor. Mars was considered the father of the Roman people, as he fathered Romulus and Remus. He also had many other attributes – the god of violence, passion, sexuality, male excellence, and beauty.

Temples in honor of Mars were erected outside the pomerium, the city’s sacred center where weapons could not be carried. In the 2nd century BC, Emperor Augustus moved the cult of the warlike god to the center of Rome and built on his forum the majestic Temple of Mars Ultor (Tempio di Marte Ultore), the remains of which have survived to this day.

Quirinus

Quirinus is an ancient god of Roman Italian origin, one of the principal patrons of Rome alongside Jupiter and Mars. He was worshiped by the Sabines, who settled on the Quirinal Hill (Colle Quirinale).

The god was identified with Romulus, who was likened to the valiant and spear-armed Quirinus (Quirīnus in Latin means “possessing a spear”). Possibly, he was initially a war god to the Sabines, but to the Romans, he represented civilian values and authority. As descendants of Romulus, Romans sometimes called themselves “Quirites,” i.e., people of Quirinus.

Today, the ancient god is commemorated by the name of one of Rome’s hills – the Quirinal (Colle Quirinale) and the residence of the President of the Italian Republic, the Quirinal Palace (Palazzo del Quirinale).

I recommend reading about the 7 hills of Ancient Rome.

The Oldest Roman Deities

Among the many Roman deities, a few of the oldest and most interesting stand out, those who were never subsequently assimilated by Greek gods. Besides Quirinus, part of the Archaic Triad, these include Janus, Saturn, and Vesta, as well as the family spirits, the Lares and Penates.

Janus

Janus was identified with primordial chaos and worshiped as the guardian of order and peace. He was depicted with two faces looking in opposite directions, simultaneously into the past and the future, symbolizing entrance and exit.

According to legend, Janus founded the city on the Janiculum hill (Janiculum) and became the first king of the Lazio region. One of Rome’s first temples, built by Numa Pompilius, was dedicated to this god.

The pagan structure had an exciting feature: during the war, its doors were open, and in peacetime, they were closed. Interestingly, under the reign of Numa Pompilius, the Temple of Janus stood with its doors closed for 43 years, indicating the peaceful policy of Rome’s second king.

Janus gave his name to January, the month that serves as a kind of entrance to the new calendar year.

Today, near the famous Mouth of Truth, you can find the Arch of Janus (Arco di Giano), dating back to the 4th century AD.

Also, on the Janiculum hill, there is one of the locals’ favorite viewing platforms, as well as monuments to Giuseppe Garibaldi, Anita Garibaldi, the fountain of Acqua Paola, and Bramante’s Tempietto.

Saturn

Saturn was a deity considered the founder of agriculture and civilization.

He is traditionally depicted as an old man with a scythe – a tool used in the wheat harvest. In antiquity, Saturn was not regarded as a local god. He came from Greece and ruled in Latium before the foundation of Rome, during the mythical golden age – a time of “lost paradise,” a happy and carefree human existence. It was he who taught the future Romans agriculture and the celebration of the harvest.

Vesta

Vesta is the virgin goddess of the family and the hearth, daughter of Saturn and Ops. She was often depicted as fire, an ancient cult that dates back to the naturalistic religious concept of the Indo-Europeans.

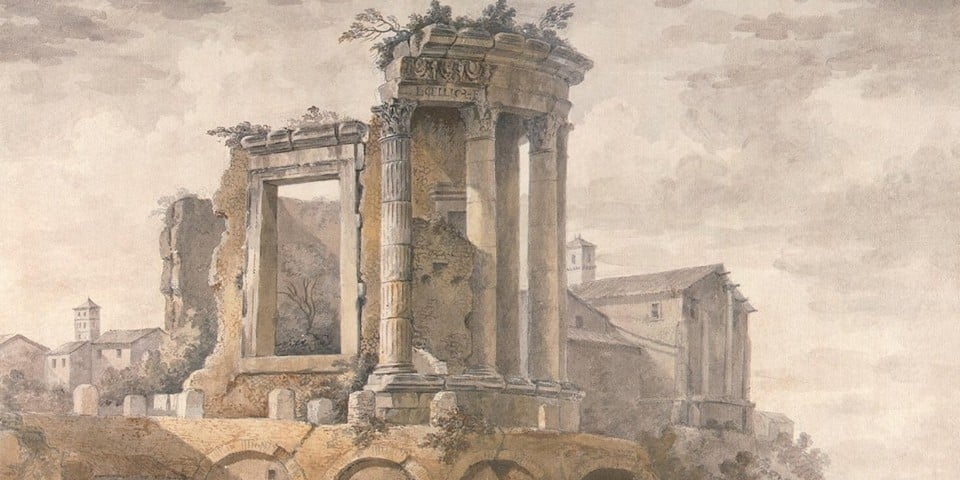

The Temple of Vesta was traditionally built by the semi-legendary king Numa Pompilius. The remains of this building can still be seen today in the eastern part of the Roman Forum, as well as in Tivoli.

In the goddess’s temple, the Vestal Virgins constantly maintained a sacred fire. It was extinguished only in AD 391 by the order of Emperor Theodosius, who fought against paganism.

Lares and Penates

Roman deities of the family, protecting the household hearth, had no analogs in other religions. The oldest among them were the Lares and Penates — undefined entities related to guardian spirits. They were depicted as figurines of two youths, identified as gods brought by Aeneas from Troy. Romans placed the Penates near the household hearth in a closed cabinet along with food to keep the food supplies safe.

Each family had its Penates, transferring them from the old house to the new one and passing them down from generation to generation.

Lares were considered protectors of the dwelling itself and the adjacent groves. They did not follow people when they moved.

Minor Gods

- Ceres — goddess of the harvest and fertility

- Consus — god of the grain seeds and underground grain storage

- Ops — goddess of fertility and wealth

- Pomona — goddess of fruits

- Fauna — goddess of nature and animals

- Flora — goddess of spring and flowers

- Robigus — Roman god of wheat rust (invoked to prevent plant diseases)

and others.

The forest deities Faunus and Silvanus ensured the protection of livestock and rural estates. The god of fertility, Priapus, associated with gardens and the protection of goat herds, fish, and bees, was known for his extravagant appearance due to his large erect phallus.

A rich harvest and family prosperity depended on natural phenomena, governed by gods with powerful energy: Vulcan — the god of destructive fire, Neptune — originally the god of freshwater, later also of the seas, Fons or Fontus — the god of springs and wells, Tiberinus — the god of the Tiber river, and Anna Perenna, the goddess of the new year’s onset.

Destructive forces of nature were overseen by Cybele, and earthquakes by Tellus, the goddess of the earth and the dead.

Romans also worshipped quite unusual deities: Vaticanus or Vagitanus — the god of crying infants, Viriplaca — the goddess of marital disputes, Orbona — the goddess of couples who lost children, Promitor — the god of distributing bread in storerooms, Vacuna — the goddess of those absent and other gods for all aspects of life.

Important: The name of the Vatican City-State is not related to the pagan deity.

The Republican Period

During the Republic, the archaic religion gradually lost its position. The development of trade relations with Greece and Etruria brought the Romans into contact with new gods, who gradually entered their lives.

New Gods

The policy of Rome did not hinder the introduction of religious cults from other peoples, provided they did not contradict the norms of generally accepted morality and did not represent any political danger. The Romans welcomed foreign gods, thus attracting the people who worshiped them to their side.

The penetration of the inhabitants of the Greek Olympus into the Roman pantheon began in the 5th–4th centuries BC through the mediation of the Etruscans. For some time, ancient Roman deities were simply associated with Greek ones, and later, they acquired their appearance and distinctive features. Thus, Jupiter was compared to Zeus, Mars to Ares, Juno to Hera, Venus to Aphrodite, Diana to Artemis, Minerva to Athena, Saturn to Cronus, Ceres to Demeter, Neptune to Poseidon, and so on.

Some Greek gods had no analogs among the Romans. These include, for example, Apollo — the god of music, poetry, and prophecy, and Asclepius or Aesculapius — the god of medicine.

The Twelve Main Deities of the Roman Pantheon

A group of twelve deities of the Roman pantheon formed the mythological Council of Gods (Dii Consentes), led by Jupiter. It included, in pairs, six gods and six goddesses: Jupiter-Juno, Neptune-Minerva, Mars-Venus, Apollo-Diana, Vulcan-Vesta, and Mercury-Ceres.

The number of characters in the Council of Gods is not accidental and has an ancient origin. In the 6th century BC, the cult of the twelve Greek gods, Olympians, led by Zeus, flourished. The most essential Etruscan god, Tinia, had as many assistants, and their prototype was the even more ancient twelve Hittite gods.

In the Roman Forum, in the 3rd or 2nd century BC, the Portico of the Consenting Gods (Porticus deorum consentium) was erected, adorned with twelve golden statues of the principal deities. It was reconstructed during the Flavian dynasty and restored in 367 AD as a monument to paganism during the domination of Christianity.

The portico on the Roman Forum can still be seen today, located between the Temple of Vespasian (Tempio di Vespasiano) and the Temple of Saturn (Tempio di Saturno), at the base of the Tabularium.

The Capitoline Triad

Three out of the twelve main Roman gods, Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva, formed the apex of the pantheon — the Capitoline Triad.

Juno

Juno was an ancient deity associated with the lunar cycle of the primitive Italian peoples.

The Romans worshiped her as the goddess of marriage and childbirth, as well as the protector of animals and patroness of Rome. After assimilation with the Greek gods, Juno came to be revered as Jupiter’s wife, assuming the role of the leading lady in the Roman pantheon.

“Moneta” was one of the goddess’s titles, signifying her functions to remind, warn, or instruct, including spending money. The Temple of Juno Moneta, whose courtyard the Romans began to mint coins, gave its name to the modern world’s term “money.”

Read more about Juno Moneta.

Minerva

Minerva — the goddess of war, borrowed by the Romans from the Etruscans, who called her “Menrva.”

Possibly, an even earlier prototype was the Greek Athena, with whom Minerva was later identified. Unlike her martial counterpart with “masculine” qualities, the virgin Minerva was also considered the goddess of wisdom and justice, the patroness of craftsmen, poets, artists, students, writers, and doctors.

According to mythology, Minerva was born from her father’s head, Jupiter, after he deceitfully swallowed the oceanid nymph Metis. Minerva was born fully grown, in armor, and already fully armed.

The Early Empire

In the first half of the Empire period (31 BC–AD 284), traditional Roman religion began to experience a sort of crisis. Meaningless numerous rituals gave way to a new religion, which was oriented towards the nature of the gods, the soul of the individual, and the search for their ultimate purpose in life.

The Imperial Cult

The imperial cult became a new direction in the religion of Ancient Rome.

The first to be honored with supreme worship was Gaius Julius Caesar. After his death, he was equated to a god and proclaimed divus – divine.

This was predicated on the legend developed by Caesar about his descent from Venus and Aeneas.

The cult of the living emperor appeared during the principate of Octavian Augustus. He considered himself the heir of the divine Caesar and, moreover, the son of Apollo, using the iconography of this god for ideological purposes.

In Rome, the cult of Augustus was developed after his death, whereas in the East, he was worshipped as a god during his lifetime. The Senate, which made the official decision, declared the emperor worthy of apotheosis – the ritual of deification.

In subsequent Roman history, each successor to power deified the deceased emperor with the Senate’s approval.

The imperial cult was also associated with abstract gods that emphasized the power and authority of the Roman Empire. Among them were Victoria – the goddess of victory, Concordia – the embodiment of the state’s citizens’ agreement, Providentia — the divine incarnation of the ability to foresee, Justitia – the goddess of justice, Pax — the goddess of peace, Bonus Eventus – the embodiment of success.

The cult of the emperors persisted until the end of the 3rd century AD, inseparable from the cult of Rome’s traditional and new gods.

Mystery Cults

Interest in the question of life after death led people to turn to the underworld gods. In the traditional religion of the Romans, various mystery cults of Eastern origin appeared, such as the cults of Cybele, Isis, Serapis, and Mithras.

The rites inherent to them were shrouded in mystery and mystical components. Initiates performed authentic theatrical performances, sometimes terrifying.

The cult of Mithras – a deity of Indo-Iranian origin, remains the most mysterious in the history of religion in Ancient Rome. Despite the artifacts and numerous underground temples of this deity preserved in Italy, Mithraism has not unveiled the secret of its teachings and practices.

The earliest evidence of the rites of the Mithraic cult in Rome dates back to the 2nd century BC, while it became widespread in the 1st–4th centuries AD. The deity was associated with sunlight, justice, friendship, concord, and the cosmos. An attractive postulate of Mithraism was the assertion that through communion with the god, a person could achieve bliss and spiritual perfection during earthly life.

According to legend, Mithras was born from a rock in a cave, so the temples of this deity – Mithraea, are primarily underground. In the 3rd century, Rome had about 800 such sanctuaries, indicating the incredible popularity of the mysteries. Today, one of the largest Mithraea has been preserved near the Colosseum under the Basilica of San Clemente (Basilica di San Clemente).

Also, today, every history enthusiast can see the Mithraeum under the Baths of Mithras in Ancient Ostia, built in the early 3rd century AD.

The Late Empire (2nd-6th centuries AD)

The need for a religion focused on the individual led the Romans to turn to Christianity.

Everything changed under Constantine the Great, who allowed free practice of religion.

Christianity replaced pagan cults and was declared the state religion by Emperor Theodosius I in 380 AD.

It is not precisely known whether the opposition between paganism and Christianity was fierce, but the old gods did not immediately leave Rome. In the 5th century, small temples of pagan gods were still being constructed in rural areas. A symbol of the old faith, the Altar of Victory erected by Augustus, remained in the Senate. The statue of the goddess was removed and reinstated several times from 357 to 394 AD. The final removal of the sculpture marked a point in the debate on tolerating the old religion in favor of Christianity.

At the same time, in the East, Theodosius issued edicts in 381 and 385 AD that prohibited sacrifices for the purpose of divination. These were the final blows to the dying paganism.

Centuries have passed, but even today, the Roman gods are present with us. They are reminded of ancient ruins, classical masterpieces, beautiful legends, the names of celestial bodies and calendar months, and many other objects and events that have become familiar.

Italy for me From Italy with love

Italy for me From Italy with love