Publius Aelius Traianus Hadrianus, widely known as Hadrian, was a Roman emperor of the Antonine dynasty who reigned from 117 to 138 AD. He was counted among the “Five Good Emperors” who ruled during the 2nd century AD, which was considered the golden age of the Roman Empire. Hadrian was a remarkable and multifaceted personality who left a significant mark in history. He showcased his talents as a skilled military commander, progressive legislator, curious traveler, and discerning art connoisseur.

Today, the great emperor is remembered through some of the world’s most famous landmarks that were built under his patronage. These include the Castel Sant’Angelo and the Pantheon in Rome, the Villa Adriana in Tivoli, and Hadrian’s Wall in Northern England.

Page Contents

The Antonine Dynasty

The Antonine dynasty, to which Hadrian belonged, ruled from 96 to 192 AD and was the third dynasty of the principate era (27 BC – 285 AD), a distinctive form of government in Ancient Rome that combined monarchical and republican elements. The Antonine dynasty stood out because five out of its seven emperors came from provincial nobility and inherited power through adoption rather than bloodline. This practice allowed for the selection of capable rulers from the political elite of the state, intellectuals, and “philosophers” who possessed a deep understanding of politics, law, and philosophy.

As history has shown, these qualities were exemplified by the five provincial emperors of the Antonine dynasty: Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, Marcus Aurelius, and Lucius Verus.

Family

Hadrian was born on January 24, 76 AD, into the family of Publius Aelius Hadrianus Afer and Domitia Paulina. According to different sources, he was born either in Rome or Italica, a Roman colony located 9 kilometers from modern-day Seville in Spain.

In this small town, the future emperor’s family had settled since the time of the Second Punic War (218-201 BC), amassing wealth through the olive oil trade. Hadrian’s father was a cousin of Marcus Ulpius Traianus (the future emperor), who also hailed from Italica. His mother, Domitia Paulina, belonged to a senatorial family whose roots were in another Roman colony, Gades (modern-day Cadiz) in the region of Andalusia. Hadrian had an older sister, Aelia Domitia Paulina, whom he did not acknowledge as his only blood relative.

Publius Aelius Hadrianus Afer moved to Rome with the hope of pursuing a political career and gaining even greater honors than he had in Italica. The first notable success in the Aelian family came with Marullinus, the great-grandfather of the future emperor, who became a Roman senator. Hadrian’s father also rose to the rank of praetor. He passed away when Hadrian was only 10 years old, entrusting the guardianship of the young boy to Publius Acilius Attianus, who would later become a powerful Roman official, and to his cousin Trajan, who was already a successful military commander at that time.

It cannot be said that Trajan harbored warm familial feelings towards Hadrian. Rather, it was his wife, Pompeia Plotina, who favored her husband’s nephew and took part in matters of his upbringing and, in the future, his career. The young boy, who likely accompanied his father on trips to Athens in his early childhood, showed a particular interest in the culture of ancient Hellenism, earning him the nickname “Little Greek.”

Furthermore, Hadrian made significant progress in the study of grammar and arithmetic, excelled in sports and hunting, and passionately engaged with music and poetry.

Emperor Hadrian’s Career

At the age of 19, Hadrian embarked on a military career, assuming the position of tribune of the Second Auxiliary Legion in Lower Pannonia. The following year, he transferred to the Fifth Macedonian Legion stationed in Moesia, and in 97 AD, he achieved a transfer to the Twenty-Second Primigenia Legion, which was formed in Germany to be closer to his guardian and future emperor.

The rapid succession of power within three years from Domitian to Nerva and then to Trajan brought Hadrian closer to the imperial circle. For an ambitious young man, a promising path in the military and later in the political sphere opened up.

Hadrian demonstrated his talent and bravery in military affairs during the First (101–102) and Second (105–106) Dacian Wars, where he accompanied Trajan. He was even awarded twice, although the specific achievements for which he received these honors are unknown.

In 107 AD, Hadrian became the governor of Lower Pannonia, and in 108 AD, he was elected consul for the first time. From 112 to 113 AD, Hadrian resided in Athens, where he acquired citizenship and was proclaimed an archon, the chief ruler of the Greek city-state.

The history remains silent about Hadrian’s feats during Trajan’s Parthian campaign in 115–117 AD. The next step in his career came in 117 AD when he was appointed as the governor of Syria and elected consul for the second time.

On August 8, 117 AD, one of the greatest Roman emperors, Marcus Ulpius Nerva Trajan, passed away in the coastal town of Selinus in Cilicia (modern-day Turkey) before he could reach Italy.

Рим готов был провозгласить нового, 14-го императора и Публий Элий Траян Адриан стал Rome was ready to proclaim a new, 14th emperor, and Publius Aelius Traianus Hadrianus proved to be a worthy choice. Throughout his life, he held the power of the Tribune of the Plebs 22 times, was elected consul 3 times, declared emperor twice (the second time in 135 AD), and at the time of his death, he held the illustrious title of Emperor Caesar Traianus Hadrianus Augustus, Pontifex Maximus, and Father of the Country.

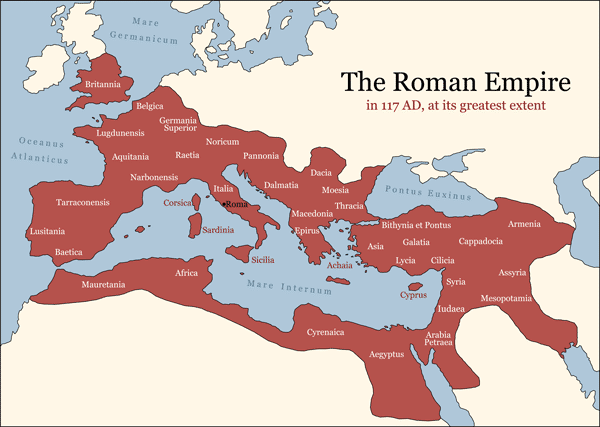

On the map below, the borders of the Roman Empire at the time of Hadrian’s accession to power in 117 AD are shown:

Appearance

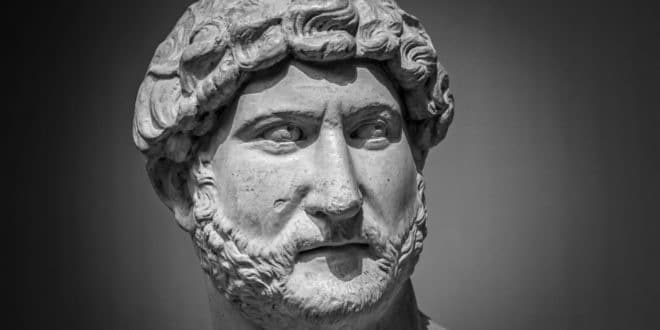

Hadrian came to power at the age of 41, which corresponds to the time when the first sculptural portraits of the emperor were created.

Over 230 works by various artists have been preserved, which idealized Hadrian’s appearance to some extent. Additionally, descriptions of his appearance have come down to us from the ancient Roman biographical manuscript “The Lives of the Caesars.”

The emperor had a strong physique and tall stature, combined with elegance. He maintained his good physical condition through horse riding, long walks, and sports exercises with weapons. Hadrian was in such good physical shape that during a hunting expedition, he personally killed a lion.

Personal Qualities

Hadrian was a multifaceted personality: he was fluent in two languages (Greek and Latin), mastered grammar and rhetoric, had knowledge of medicine and astronomy, and also found time for singing, playing stringed instruments, painting, and sculpture. He had a phenomenal memory that became the subject of legends. Hadrian knew the names of all high-ranking officials in his entourage and each legionary he interacted with. After reading any text once, he could recount it accurately. Biographers compared Hadrian to Caesar in his ability to simultaneously write, dictate, listen, and converse with his friends.

However, a spoonful of tar was present in the contradictory character of the emperor. In “The Lives of the Caesars,” the following can be read about him: “He was strict and cheerful, friendly and majestic, frivolous and deliberate, stingy and generous, a master of hypocrisy and pretense, cruel and kind, brief, always and in all respects changeable.”

Accession to Power

Hadrian was recognized as adopted after the death of Trajan. The letter in which the dying emperor supposedly named him his adopted son raised doubts about its authenticity. The copy of the letter that reached Rome was signed only by Trajan’s wife, Plotina. She and Publius Acilius Attianus (Hadrian’s second guardian) were present at Trajan’s deathbed in Selinus and decided to forge the will in favor of their beloved ward.

Hadrian, who received the long-awaited news of his adoption by Trajan on August 11, 117, was immediately proclaimed emperor by the Syrian legion, and the Senate had no choice but to acknowledge this fact.

Once the public ceremonies dedicated to the “divine election” of the new emperor were over, Hadrian first dealt with the opposition. This included high-ranking friends and supporters of Trajan who, by their status, could have aspired to the imperial position and continued the expansionist policies of their predecessors. Under Hadrian’s tacit direction, four senators were executed, and no attempts to justify themselves helped – his reputation and relationship with the Senate were tarnished for the rest of his reign.

The minting of coins with the image of Emperor Hadrian began, including gold quinarii (quinarius aureus) and silver denarii.

Reign

The rule of the peace-loving Hadrian greatly differed from the conquering policy of Trajan, although both “good emperors” aimed to strengthen the power of the Roman Empire. While Trajan sought to expand its territory through military conquests, Hadrian’s goal was to strengthen the external borders, preserve peace, and create stable conditions within the state.

Strengthening External Borders

In the first year of his reign, Hadrian decided to change the foreign policy of the Roman Empire. He relinquished the provinces of Assyria and Mesopotamia, returning the lands to the Parthians, and also gave up complete control over Armenia, preserving only its status as a Roman protectorate. The majority of the territories north of the lower Danube, conquered by Trajan, were abandoned and handed over to the Dacians.

The main task for Hadrian became the reinforcement of stable borders in Europe that could be easily defended.

Hadrian’s Wall

From the Author:

It is a well-known fact that Hadrian visited all the provinces of the Roman Empire. I have always dreamed of retracing Hadrian’s journey to the northern borders of his dominions, to see with my own eyes and experience the scale of the largest ancient monument that has survived to this day.

Today, to reach Hadrian’s Wall, it is sufficient to take a flight of just a few hours to Newcastle, UK. Direct flights are available from Bergamo Airport in northern Italy through www.ryanair.com. It took the emperor himself several weeks to embark on such a journey 19 centuries ago.

From Newcastle, you need to take a train to Hexham or Haltwhistle, and from there, you can reach one of the stops along the wall by the special AD12 bus.

- Official website of Hadrian’s Wall: hadrianswallcountry.co.uk

Suppression of the Jewish Rebellion

The bloodiest event during Hadrian’s reign was the brutal suppression of the Jewish rebellion from 132 to 135 AD. The cause was the emperor’s desire to restore Jerusalem, which had been destroyed in the war of 66 to 73 AD, as a Roman colony. He intended to build the Temple of Jupiter on the sacred Temple Mount of the Jews, abolish the Sabbath and circumcision, and impose Roman traditions and rules in the city.

Simon Bar Kokhba, a Jewish military leader who gained fame as the “second messiah,” openly opposed such assimilation of the Jews. His well-organized army of believers defeated a Roman legion of 4,000 soldiers, which forced Hadrian to take the harshest measures. The emperor decided to wipe Judea off the face of the earth. As a result of the suppression of the rebellion, approximately 580,000 Jews were killed, 50 fortified cities and 985 villages were destroyed (these numbers are disputed), and Jerusalem itself was renamed “Aelia Capitolina.” Hadrian banned the Jewish calendar and Halakha (Jewish law), ordered the burning of sacred scriptures, and executed Torah scholars.

Jews were prohibited from entering the city under the threat of death, with rare exceptions for Christians and on the fast day of Tisha B’Av. This order remained in place until the 4th century when Constantine the Great repealed it, restoring the city’s old name.

Hadrian did not consider this victory glorious and refused to accept a triumph from the Senate, but instead accepted the title of emperor for the second time from the army.

Domestic Policy

Hadrian demonstrated his leadership not only in strengthening the borders of the Roman Empire but also in state governance by implementing a series of profound and radical reforms.

In 131 AD, the renowned Roman jurist Publius Salvius Julianus, under Hadrian’s orders, revised the most important document of Roman law, the “Edict of the Praetor” (Edictum praetoris), which had previously been reviewed and approved annually. The emperor transformed it into a collection of permanent rules with unconditional enforcement in the future. This document, known as the Edictum perpetuum (“Perpetual Edict”), became a crucial milestone in the evolution of Roman civil law.

The emperor’s new laws improved the position of slaves, granting them legal protection. Owners could no longer simply kill a slave for misconduct, nor could they castrate or sell them to gladiator schools or brothels.

Tolerance towards Christians became more lenient, and they could now expect impartial treatment in legal proceedings regardless of their religion.

Orphans were given the right to inherit a portion of their deceased parents’ property, and unmarried women were entitled to a share of their spouse’s estate.

The emperor introduced clothing standards and strict gender segregation for attending theaters and public baths.

Reforms implemented in the army improved the conditions of Roman soldiers. Age restrictions were imposed, and bribes to tribunes were eliminated. Weapons and equipment for soldiers were also enhanced.

Construction

Unlike other emperors, Hadrian did much to maintain the prosperity of the provinces. He allocated significant funds for the restoration of structures that were damaged by earthquakes and rebellions. In commemoration of a successful bear hunt, Hadrian even founded the city of Adrianoupolis in Moesia. While staying in Athens, he ordered the completion of the Temple of Zeus, the construction of new buildings, and the installation of an aqueduct.

Hadrian admired the ancient cities of the provinces and drew inspiration from their architecture when planning the construction of new structures in Rome.

In 125 AD, he ordered the restoration of the Pantheon, which had been destroyed by fire 40 years earlier. In 136 AD, he personally participated in the development of the project for the Temple of Venus and Roma (Tempio di Venere e di Roma), which he decided to build on the site of Nero’s Golden House portico.

Between 118 and 134 AD, amidst olive groves near Rome, the emperor constructed a magnificent countryside residence known as Villa Adriana (Villa Hadriana).

The ambitious project of the architects skillfully blended with the uneven landscape, featuring original forms and exquisite construction techniques.

The grand Mausoleum of Hadrian, later known as the Castel Sant’Angelo, was completed after the emperor’s death, in 139 AD.

Initially, the colossal family mausoleum had a more elegant and grandiose appearance, and the bronze chariot with the sun god emperor atop served as a final vibrant tribute to Hadrian’s glory.

Personal Life

Hadrian’s romantic relationships were criticized even during his lifetime. His marriage to Vibia Sabina was more of a political union and did not bring happiness. The emperor was interested in beautiful young men and married women, showing a lack of moral restraint even towards his friends.

The Youth Beloved and Celebrated by Emperor Hadrian

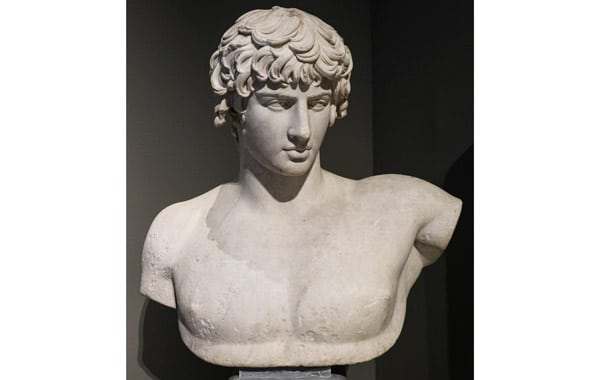

The love of Hadrian’s life was the beautiful Greek youth Antinous. Hadrian encountered him during his travels when the boy was around 12-13 years old. He captivated the emperor with his intellect and beauty. The new favorite accompanied Hadrian everywhere, but their relationship was kept discreet, and their romantic connection was only speculated upon.

Little is known about Antinous, except that he was incredibly beautiful and devoted to his friend. Antinous drowned in the Nile in 130 AD under mysterious circumstances. It is possible that it was a ritualistic suicide to save Hadrian from a prophesied death.

The emperor mourned his beloved for a long time and then ordered priests to proclaim him a deity. Antinous, as a mortal hero, was worshipped in Egypt, Greece, and Italy. In honor of the youth, Hadrian founded the city of Antinopolis near the place of his death, established sporting games, constructed several temples, and commissioned numerous sculptural portraits, many of which have survived to this day.

The melancholic image of the young man with beautiful facial features and an athletic figure is preserved in exquisite busts and statues, of which there are over 5,000.

Death of Emperor Hadrian

In his final years, Adrian suffered from a severe illness, possibly heart failure, and even made several attempts to end his own life. He appointed his successor twice. The first, the brilliant senator Lucius Aelius Caesar, died prematurely, after which the emperor adopted Antoninus Pius. He became the next ruler of Rome and the one who ensured proper honors were paid to Adrian.

Publius Aelius Hadrianus passed away on July 10, 138 AD, at the age of 62, at his villa in Baiae. The cause of death was likely pulmonary edema after Adrian consumed a large dose of pain medication. Initially, the emperor was buried in Puteoli at a residence belonging to Cicero, and later his body was transported to Rome. In 139 AD, Adrian’s remains were cremated, and his ashes were placed in the completed mausoleum, where his wife Vibia Sabina and adopted son Lucius Aelius Caesar also found their final resting place.

Shortly before his death, Adrian wrote lines full of sadness and despair:

“O trembling soul, tender wanderer,

Guest and friend in this human body,

Where do you now wander,

Weakened, chilled, defenseless,

Unable to play as before?”

Interesting Facts about Emperor Hadrian

- Hadrian ruled as the Roman Emperor from 117 to 138 CE, succeeding Emperor Trajan. He was known for his travels, which included visits to nearly every province of the Roman Empire.

- Hadrian is famous for ordering the construction of Hadrian’s Wall in Britain. This massive fortification spanned 73 miles (117.5 kilometers) and marked the northernmost frontier of the Roman Empire.

- He was an avid patron of the arts and architecture, with the Pantheon in Rome being one of his most notable projects. The Pantheon, completed in 126 CE, is a masterpiece of Roman engineering and continues to be an architectural marvel today.

- Hadrian is remembered for his extensive reforms and efforts to codify Roman law. He commissioned the compilation of the “Edictum Hadriani” to clarify and streamline legal practices within the empire.

- Under Hadrian’s reign, the Roman Empire experienced a period of relative peace and stability known as the Pax Romana. His diplomatic approach and focus on strengthening the empire’s borders contributed to this era of tranquility.

- Hadrian was known for his fascination with Greek culture and is credited with the widespread adoption of Greek architecture and art styles throughout the Roman Empire. This fusion of Roman and Greek influences became known as the “Hadrianic Renaissance.”

- Despite his accomplishments, Hadrian faced several challenges during his reign, including rebellions in Judea and Britannia. He successfully suppressed these uprisings and implemented policies aimed at maintaining Roman control over these regions.

Italy for me From Italy with love

Italy for me From Italy with love