Roman coins were an integral part of the monetary system of Ancient Rome, originating in its Royal Period of rule and fading away in the late years of the Empire. This Period, spanning more than ten centuries includes the fascinating story of the transformation of shapeless metal pieces into the minted coins of the great Roman Empire.

Page Contents

Bronze Age Money: Aes Rude

Commodity-money relationships existed on the Apennine Peninsula as early as the Bronze Age. Tribes inhabiting the territory of modern Italy used items made of iron and copper — metals whose deposits were accessible in their lands — as currency. Initially, these were arrowheads, work tools, and various household utensils. Later, they were replaced by pieces of metal, which essentially became equivalents and measures of commodity value.

The Roman protocoin is considered to be the ingot of unprocessed bronze — aes rude (literally, ‘rough bronze’), consisting of a copper-tin alloy.

The oldest examples of such currency, found in the lands of central Italy, date back to 3000-2000 BC. The unique feature of aes rude was its weight, ranging from 1.1 lbs (0.5 kg) to 6.6 lbs (3.0 kg). These heavy currencies were inconvenient for transactions, requiring constant weighing and secure storage spaces.

Royal Period (753-509 BC): Aes Signatum

During the Royal Period of rule in Ancient Rome, bronze remained the medium of exchange, but it had already acquired distinctive features of different values, laying the groundwork for the future monetary system. Trade with the more advanced Etruria and Greek polises in southern Italy required Rome to denote the denomination of money and make it an “international currency.”

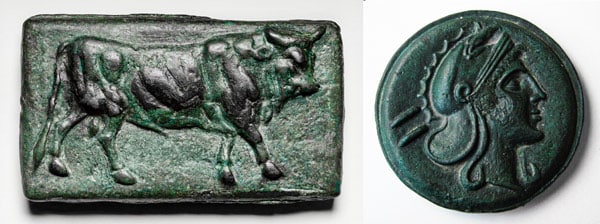

Replacing the shapeless aes rude were aes signatum (literally, ‘marked, having a sign’) – rectangular bronze ingots with stamped images.

These presumably appeared in central Italy in the 6th century BC and were of comparatively high quality. Aes signatum did not require weighing, as the ingot indicated their value. The images on both sides depicted ritual objects or animals, reflecting a nod to the barter system of previous centuries.

Republican Period (509-31 BC)

The monetization of trade relations in Ancient Rome took root in the Republican Period. This era marked the introduction of a system for equating monetary units with the circulation of copper, bronze, silver, and gold coins.

Bronze Coins: Aes Grave

The first round-shaped Roman coins, made of bronze and copper, began to be cast towards the end of the 3rd century BC. These were known as a grave, translating to ‘heavy bronze.’

These coins were likely initially crafted by Greek artisans in city-states like Naples, Paestum, Croton, Sybaris, Metapontum, and Tarentum. Romans traded these coins with neighboring states, while central Italian cities minted their own for local use.

The First Punic War (264-241 BC) dictated the need for Rome to establish a uniform monetary system. Aes grave, initially heavy and varied in appearance, gradually acquired a standard weight and design. The benchmark coin of the aes grave was the as or ass (from Greek ais, meaning ‘one’). It weighed a libra – 327.4 grams or about 12 ounces. The as became the Roman standard of weight and the most widespread currency unit for centuries.

Smaller denominations derived from the as were also minted for easier transaction handling, segmented into 12 parts: semis (1⁄2), triens (1⁄3), quadrans (1⁄4), sextans (1⁄6), bes (2⁄3), quincunx (5⁄12), semuncia (1⁄24), and uncia (1⁄12).

Due to inflation and the nominal weight reduction of the as from 327.4 grams to 13.6 grams in 89 BC, multiples of the as were introduced — dupondius (2 asses), sestertius (2+1/2 asses), tressis (3 asses), quadrussis (4 asses), quincussis (5 asses), and decussis (10 asses).

The coinage’s exterior design changed over time but maintained unique characteristics. The obverse, or front side, usually featured deities – Janus, Saturn, Minerva, Hercules, Mercury, and Roma. The reverse side was consistently designed with the image of a galley’s prow (rostrum). This depiction of a warship part symbolizes the Greek influence on Roman currency, as similar designs were prevalent on coins of the Hellenistic Era.

Silver Coins

The development of trade relations with the Greeks in southern Italy highlighted the need for the introduction of silver into the commodity circulation – a metal from which the primary coin of the Mediterranean and the Near East, the drachma, was made.

Precursors to the Denarius

The Romans began minting coins from white precious metal similar to the Greek drachma in 269-268 BC, five years before the start of the First Punic War. One such coin, called “didrachm,” weighed 6.81 grams and corresponded to two Greek drachmas.

A coin of similar value was the quadrigatus – a Roman silver coin minted between 235-211 BC. Its name referred to the depiction of a quadriga, a chariot drawn by four horses, presumably the one atop the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus, established in 296 BC.

The didrachm and quadrigatus were minted in small batches in southern Italy due to silver scarcity and were used either for purchasing military equipment or for paying soldiers fighting for Rome against Carthage.

The victoriatus was another silver coinage introduced slightly later, around 221 – 170 BC. Weighing 3.41 grams, half the weight of a didrachm, it depicted Jupiter on the obverse and the goddess of Victory placing a wreath on trophies on the reverse.

These coins were minted outside Rome (presumably on the island of Corfu) and specifically for circulation in conquered territories.

The Denarius

The denarius (from the Latin denarius, meaning ‘consisting of ten’) became the quintessential Roman silver coin. As archaeological finds suggest, the first batch was likely minted in 211-212 BC on the island of Sicily.

The original weight of the silver coin was 4.55 grams, and its value was equivalent to ten asses, as reflected in the name and the sign X. The obverse featured the head of the goddess Roma in a helmet or Jupiter, and the reverse depicted the Capitoline She-Wolf, nursing Romulus and Remus, or the twin brothers Dioscuri.

Rome also minted other smaller denomination silver coins for a while: the quinarius (quinarius), equivalent to ½ a denarius or 10 asses, and the sestertius (sestertius), corresponding to ¼ of a denarius or 2 ½ asses.

The devaluation of the denarius began in 141 BC. As a result of monetary reform, its ratio to the as was no longer 1:10, but 1:16. The updated denarius, weighing 3.9 grams, was marked with the sign XVI.

Over time, the denarius gradually devalued, losing its weight and quality, but it remained one of the main coins of Rome until the end of the 3rd century AD.

Gold Coins

In the Roman Republic, alongside the silver denarii, gold coins – aurei (from the Latin aureus, meaning ‘gold’) – were also in circulation. Trade with the East and the city-states in southern Italy dictated Rome’s adoption of the Greek monetary system, where coins made of precious metals were predominant.

The First Aurei

In the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC, gold coins were minted irregularly and in small quantities, usually during wartime for rewarding soldiers or conducting foreign trade. The Romans conserved their gold reserves, acquired as war trophies and tributes.

The first aurei, weighing 6.81 grams, appeared in 286 BC, presumably in the Campania region or on the island of Sicily. During the Second Punic War (218-201 BC), to cover military expenses, a series of aurei was made, consisting of three coins of equal design but different values – 20, 40, and 60 silver sestertii, weighing 1.1, 2.2, and 3.4 grams, respectively. Interestingly, the gold for these aurei came from reserves accumulated during the First Punic War.

On the obverse of the aureus was an image of the god Mars and an eagle with lightning on the reverse. The denominations of the coins were marked with the numerals XX, XXXX, and LX.

After the Second Punic War ended, Rome ceased the minting of gold coins for almost a century and a half, resuming it sporadically to fund military campaigns.

Apologies for the oversight. Here is the revised translation with HTML characters visible and maintained in their original format:

Aurei of Caesar’s Era

Regular minting of aurei commenced in the latter half of the 1st century BC, after the conquest of Gaul and its affluent gold mines.

In 49 BC, Julius Caesar, having gained full access to the state treasury, initiated the minting of the most giant batch of coins in Roman history.

Caesar standardized the weight of the aureus at 1/40 of a pure pound of gold (327.45 grams), equating to 8.19 grams. This was the largest pure gold coin, equal in value to 25 silver denarii or 100 sestertii.

Currently, approximately 272 varieties of Caesar’s aurei are known. The reverse often displayed the imperial laurel wreath, while the obverse usually showed godly profiles.

Venus, for instance, signified the Julian family’s origin legend, and Ceres and Bacchus symbolized the allocation of inexpensive bread and wine. Having declared himself a lifelong dictator and emperor, Caesar started depicting the ruler’s likeness on the obverse.

After Caesar’s assassination in 44 BC, each of his rivals commenced minting their own gold coins for distribution to soldiers to gain their allegiance. The gold coins from this Period feature images and symbols of Octavian, Mark Antony, Brutus, Cassius, Pompey, and his two sons. These coins are highly prized among numismatists for the realistic portraits of these notable historical figures.

Imperial Period (27 BC – AD 476)

During the Imperial Period, Ancient Rome reached the peak of its power, which would not have been possible without a robust financial system. The emperors who succeeded each other carried out various reforms, including monetary ones, which became indicators of their successful or failed reigns.

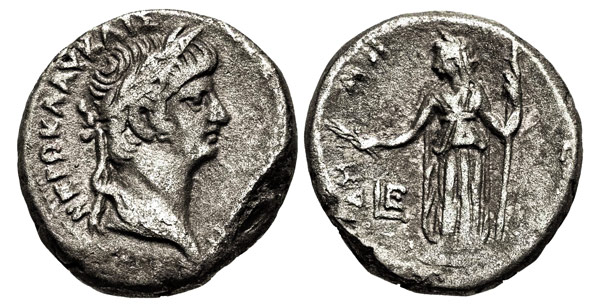

Reform of Octavian Augustus

The monetary reform conducted between 23 and 20 BC by the first emperor, Octavian Augustus, organized the Roman monetary system. Coins of different denominations were regularly minted in large quantities, stimulating trade and contributing to the prosperity of the entire Roman Empire.

Augustus continued minting half aurei and denarii – the gold and silver quinarius, which Romans first saw during Julius Caesar’s triumph in 45 BC.

During the time of Octavian Augustus, brass — an alloy of copper (80%) and zinc (20%), known in Ancient Rome as “orichalcum” — was introduced alongside pure copper. Red copper was used for the as, semis, and quadrans, while “yellow copper” (i.e., brass) was used for the sestertius and dupondius. The triens, sextans, and uncia simply disappeared from circulation.

The nominal value of the coins stabilized in relation to the denarius in the following ratio:

| Denarius | 1 |

|---|---|

| Aureus | 25 |

| Golden Quinarium | 12½ |

| Silver Quinarium | ½ |

| Sestertius | ¼ |

| Dupondius | 1/8 |

| Ass | 1/16 |

| Semis | 1/32 |

| Quadrans | 1/64 |

The reverse featured scenes from mythology, events from Augustus’s life, architectural monuments, zodiac signs, and sacred symbols of religious cults. Everything was intended to remind Romans of the emperor’s greatness and divine selection.

Unsuccessful Reforms and New Coins

Each subsequent monetary reform was a stage in the development of the coinage system of Ancient Rome, but not all of them yielded the expected results. The reforms under emperors like [Nero](https://en.italy4.me/history/roman-emperors/nero.html), Caracalla, and Diocletian can be considered unsuccessful. Attempting to earn the trust and respect of the people while reducing treasury expenses, they implemented a series of unpopular measures.

In 64-65 AD, Nero reduced the gold content in aurei by 0.513 grams and the silver content in denarii by 0.48 grams, maintaining their previous ratio.

For lower denomination coins, copper was replaced with cheaper brass. In addition to reducing weight, the silver content in denarii was also reduced by introducing a 10% alloy (mixture of impurities). This was not publicly announced, but the debasement of the coins was evident, further tarnishing the reputation of Roman money.

Caracalla, obsessed with the glory of Alexander the Great, depleted the treasury with endless wars to the point that he had to reduce the silver content in denarii by 25%.

The emperor’s introduction of a new coin in 215 AD, the antoninianus, nominally equal to two full denarii, did not remedy the situation. Gradually, the new currency devalued and turned into bronze coins, merely coated with a thin layer of silver. The denarius value also plummeted, its ratio to the gold aureus falling from 1:25 to 1:50 and, by the end of Caracalla’s reign, to 1:800.

Diocletian’s Monetary Reform

Diocletian’s monetary reform, conducted between 286-294 and 301 AD, responded to rapid devaluation caused by wars, poor harvests, epidemics, and the depletion of silver mines in the provinces. The emperor revived the minting of “good” coins by increasing the gold content in aurei and silver in denarii. Diocletian named the updated white precious metal coin the argenteus (Argenteus), which simply means “silver.”

Caracalla’s antoninianus was replaced by the follis (follis) – a new bronze coin weighing about 10 grams. However, the reform did not achieve the expected success.

The Romans, distrusting the authority, preferred to hoard gold and silver coins for a rainy day, resulting in the disappearance of the new currency and a sharp increase in black market prices. Diocletian eventually rescinded his decree, but it failed to stop the crisis.

A complete list of my favorite books about Italy and Rome can be found in this article.

Reform of Constantine the Great

Constantine the Great, who ruled from 309 to 324 AD, improved upon Diocletian’s monetary reform and halted rampant inflation. There were several reasons for this success. The treasury was replenished with silver and gold acquired in wars by the previous ruler. The new Christian religion allowed for the destruction of pagan temples and confiscated their numerous gold, silver, and bronze statues in favor of the imperial state, which were then melted down into money.

The Christian emperor first began minting his gold coin – the solidus, weighing 4.55 grams. Its derivatives were the semis (1/2 solidus) and the tremissis (1/3 solidus). The new silver coin, the miliarensis, was tied to the value of a pound of gold as 1/1000 of its part and maintained a solid ratio of the two precious metals. The coin worth ½ miliarensis was called the siliqua (1/1728 of a pound of gold).

Soon, the silver-plated bronze follis, weighing 1.94 grams, was replaced by the centenionalis, weighing 5.15 grams. Later, a coin called the maiorina (“large coin”) was minted, worth 1/60 of a solidus. The previous aureus and denarius were no longer produced.

The solidus remained the principal monetary unit of the Roman Empire until the fall of Byzantium in 1453.

I recommend reading about the causes of the fall of the Roman Empire.

Interesting Facts about Roman Coins

- The first mint in Rome was established around 269 BC near the temple of Juno Moneta on the Capitoline Hill. The Romans considered this location most suitable, as the goddess was regarded as the patroness of money. Soon, the word “Moneta” entered most European languages, becoming synonymous with the products of the masters who minted coins.

- It is hypothesized that the Roman coin sestertius became the prototype for the symbol of the U.S. dollar. The sestertius was denoted by the abbreviation IIS or IIS, where II is the Roman numeral for two asses, and S is the first letter of the word semis, indicating half an as. In abbreviated writing, the number overlapped the letter, forming the now-familiar dollar sign – $.

- The audacity in the design of Brutus’s aurei was the depiction on the reverse of two swords — the weapons used to kill Caesar, along with the inscription Eidibus Martiis (“The Ides of March”), marking the dictator’s death date. Brutus’s gold coin is the most expensive aurei sold at auction, valued at 3.5 million dollars in 2020.

- It’s interesting to compare prices in denarii for a specific period, for example, the second half of the 1st century BC, at the end of the Roman Republic. Thus, a legionnaire or unskilled worker earned one denarius daily, the same cost as a loaf of wheat flour bread. A young slave was valued in the market at 4,000 denarii, and a beautiful slave girl at 6,000 denarii. Taking the average cost of bread in Italy in 2022 – 2 euros – as a comparison, one can approximate the purchasing power of a denarius.

- Currently, the name of the currency in many Arab countries and some European states is derived from the Latin word denarius – dinar in Tunisia and Algeria, denaro in Italy, dinero in Spain, dinheiro in Portugal, denar in Slovenia, etc. The first letter d from Denarius was used as an abbreviation for the British penny until 1971.

Italy for me From Italy with love

Italy for me From Italy with love