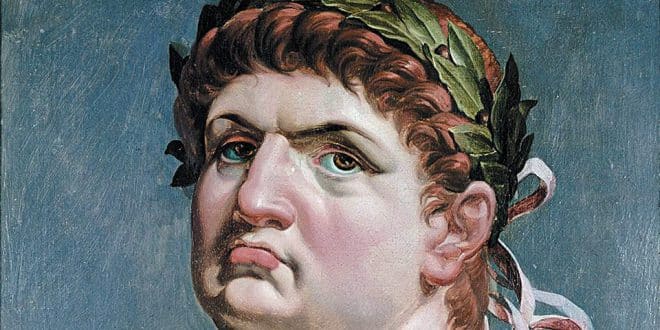

Nero – one of the most famous Roman emperors who ruled the state from 54 to 68 AD.

Ancient history knows many infamous rulers, but it is difficult to find a more controversial and contradictory figure among them. On one hand, he was a despot, a cruel murderer, and an uncompromising tyrant in his later years, but on the other hand, he was an artist, a poet, and a reformer who earned the love of the people at the beginning of his reign.

Nero sentenced his own mother, one of the chief Christian apostles, Peter, and thousands of other people to death. However, the emperor made a significant contribution to the development of Rome’s architecture by rebuilding the Eternal City after the devastating fire of 64 AD. According to classical historiography, Nero was blamed for initiating this disaster, but many modern historians convincingly refute this fact.

What was this famous emperor really like, and what led him to such a tragic end?

Page Contents

Childhood and youth

The early years of his life had a great influence on shaping the personality and character of the most famous ancient despot. It was during his childhood that the negative traits were formed and solidified, which would later turn Nero into a villain, a debauchee, and a murderer.

Birth of the future emperor

On December 15, in the year 37, a son was born into the family of Agrippina (Julia Agrippina) and Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus.

It was there that he received the news of the birth of his only son, which did not evoke the slightest enthusiasm from the young father. Gnaeus did not bother to return to Rome for the acknowledgment of paternity, which traditionally took place on the ninth day after the baby’s birth.

The father did not participate in the further life of his son and died when the child was three years old.

The mother was also absent during the crucial early years of Nero’s life.

Agrippina, who gave her firstborn the name Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus, soon after his birth in the year 39, was sent into exile with her own brother, Caligula. The accusation of conspiracy against the emperor served as the reason. Agrippina’s new home became the island of Pandateria (modern Ventotene), where the ambitious young woman prepared to fade away in anticipation of old age slowly.

Young Nero was raised by his aunt Domitia Lepida (Domitia Lepida), who treated him with tenderness but could not fully replace his mother.

Education and Upbringing. The Role of Agrippina

Since Lucius was considered one of the contenders for the throne, his education received due attention. In terms of morality, the future emperor was deprived – his teachers treated him as an adult, showing no signs of attachment. He did not know his father, and his mother, upon her return from exile, focused on her personal life.

The emotional deprivation greatly influenced the formation of the character of the future tyrant, making him a selfish individual devoid of attachment and unable to love.

The first step towards power was a successful marriage – Agrippina became the wife of the distinguished and wealthy Roman orator, Passienus Crispus. Her main goal was the throne of the Roman Empire, which she dreamt of placing her son on, to rule in his name.

Agrippina faced an obstacle in the form of Claudius’ promiscuous wife, Messalina (Valeria Messalina), who held great influence and did everything possible to eliminate her rivals. The woman even attempted to assassinate young Nero, which, however, failed. Seeing that Agrippina’s and Nero’s positions were strengthening, Messalina decided to elevate her lover, Gaius Silius, to the throne. The conspiracy was uncovered, and the emperor’s wife was executed in the year 48.

Nothing could hinder Agrippina’s ambitious plans. Having secured the support of the Romans, she surpassed her rivals in the struggle for the role of Claudius’ new spouse. Marrying her uncle in the year 49, Agrippina focused on achieving her main goal. Lucius was adopted by Claudius in the year 50 under the name Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus. Nero married the daughter of Emperor Octavia, Claudia Octavia. Unfortunately, the young man showed no interest in his wife and, moreover, harbored hostility towards her.

Personal Qualities and the Influence of Seneca

Even at that time, Nero was known as a corrupt and immoral individual, devoid of moral and ethical norms. The blame for this does not solely lie with Nero himself. Ambitious Agrippina, in her endless pursuit of power, failed to notice her son and ignored his feelings. The mother remained consistently cold towards the boy, and even as Nero grew up, she continued to dictate her will, demanding unquestioning obedience from her son.

Gradually, it became clear that Nero possessed a keen intellect, unfortunately, unsuited for governing the state. The boy enjoyed creative pursuits such as poetry, music, painting, theater, and wood carving, which his mother deemed meaningless. Agrippina compelled her son to study the sciences necessary for his future successful rule over the empire.

Nero’s chief tutor was the renowned scholar Seneca (Lucius Annaeus Seneca). Researchers still do not have a definitive opinion on the role the philosopher played in shaping Nero’s tyrannical personality. Some believe that Nero was kind and gentle towards his mentor and that Seneca lacked sufficient influence to eradicate Nero’s negative inclinations. Others convincingly argue that Seneca’s character was ambiguous: contemporaries considered him a flatterer and deceitful person, prone to the same depraved pleasures as his young protégé.

Agrippina wielded immense influence in the Empire. She controlled all state affairs, actively participated in shaping foreign and domestic policies, and enjoyed numerous privileges.

Feeling threatened by her husband’s power, she decided to have him killed. Claudius was poisoned, and in October of 54 AD, Nero became the sole ruler of the Roman Empire.

The following year, the young emperor eliminated Britannicus, the last potential contender to the throne, resorting to the familiar method of poisoning.

The Early Years of Nero’s Reign

Despite Nero’s bad reputation and a decadent and indulgent lifestyle, the early years of his reign were relatively calm and productive. Partly, this was due to the fact that Nero was barely 17 years old when he came to power.

The Politics of Burrus and Seneca

During this time, three individuals had a significant influence on him: his mother, his teacher Seneca, and the prefect of the Praetorian Guard, Sextus Afranius Burrus. The latter obtained his position thanks to Agrippina’s support, initially favoring him. It was Burrus who wielded real military power in Rome during those years. After the death of Claudius, he brought the young Nero to the Praetorian Guard, instructing them to hail him as the emperor.

The alliance between the two closest associates of the emperor, Seneca and Burr, was unique: they not only avoided rivalry but also managed to create a strong party that adhered to a constitutional policy.

- The functions of the Senate and the emperor were clearly defined, with the Senate making decisions on all major domestic policy issues.

- Taxes and penalties were reduced.

- Import duties on foodstuffs transported by sea were abolished.

- Corruption was fought against by appointing representatives from the middle class instead of the aristocracy as tax collectors.

- Educational institutions and theaters were constructed.

- Freedmen were supported.

- Repressive measures were absent.

Such measures ensured the support of the Senate for Nero and gained the sympathy of the common people.

The conflict between two factions

In the early period of Nero’s reign, the second driving force behind the state was his vain mother, supported by her lover, the influential freedman, Pallas.

These two factions, Agrippina and Burr with Seneca, were constantly at odds and vied for influence over the emperor. To achieve their goals, those close to Nero spared no methods: they engaged in cunning psychological games, successfully targeting Nero’s vulnerabilities. Flattery, feigned patronage of Nero’s theatrical pursuits, and an interest in his romantic escapades were all employed.

Nero soon became burdened by Agrippina’s excessive control and was troubled by his mother’s immense influence on the empire. Over time, this dissatisfaction evolved into a significant conflict between mother and son. Agrippina found support in Octavia, the young wife of the emperor. The conflict escalated in 55 AD when Nero became infatuated with the freedwoman Acte. The influence of the young woman on the young emperor worried his mother and wife. Agrippina threatened to reveal to the Romans the truth about the dishonorable methods Nero used to come to power.

Although the young man never married Acte, fearing his mother’s wrath, this affair ultimately shattered their relationship.

Emperor’s Love Affairs

Legends circulated about Nero’s extravagant lifestyle and incredible debauchery. Romans were never known for their strict morals, but Nero surpassed all his contemporaries.

It is known that for a period of time, Nero was married to his slave, a very young boy. He himself often took on the role of a wife for his freedman Doriphorus, a mockery of traditional family values that shocked the Romans.

Another woman who played a significant role in the emperor’s fate was Poppaea Sabina. Poppaea belonged to a noble class, was exceptionally beautiful, and equally licentious.

When Nero first laid eyes on her in 58 AD, he was struck by Poppaea’s beauty. Soon, she became his mistress, despite being the wife of one of Nero’s closest allies, Otho. However, this ambitious beauty wanted more – she thirsted to become empress.

Desiring to reclaim her lover, Poppea presented him with an ultimatum: either he would marry her, thus disposing of his wife and mother, or the fair-haired beauty would forever leave Rome.

Nero, who had long yearned to break free from his mother’s domineering control and had come of age, chose the former option.

The Murder of Agrippina

Since Agrippina enjoyed immense influence among the Romans, Nero was hesitant to openly confront her. The first attempt to remove his mother from power was a fabricated accusation of conspiracy against her, which proved unsuccessful in 58 AD.

Frustrated by this failure and under pressure from Poppea, Nero resolved to murder Agrippina.

A ship was constructed to transport the emperor’s mother during a festive occasion, with the intention that it would collapse during the voyage. However, the cunning plan failed—Agrippina, who was a proficient swimmer, managed to escape. Frightened, she made her way to one of her country estates accompanied by a maid.

Upon learning of the turn of events, Nero was consumed by rage and terror. The emperor was well aware that his mother would seek revenge. Garnering the support of his closest associates, he dispatched a squad of armed soldiers to eliminate Agrippina.

This time, the plan succeeded—Nero’s mother, who had done so much to secure his rise to power, was assassinated by the emperor’s soldiers on March 23, 59 AD.

It cannot be said that Nero took the murder of his mother lightly. He feared the anger of the people and the consequences of matricide, tormented by remorse. Later, he admitted that the image of Agrippina often haunted him, terrifying and tormenting his sanity.

Contrary to expectations, the Senate and common Romans reacted rather indifferently to Agrippina’s death. Seneca wrote a speech for Nero on this occasion, stating that killing Agrippina was a necessary step. The former empress was accused of plotting against her son’s life.

Having rid himself of his mother, Nero sent the meek and compliant Octavia into exile, accusing her of infertility. In 62 AD, the unfortunate Octavia was killed by the emperor’s order, who then finally married Poppea, the woman he had long awaited.

Tyranny during the second period of rule

The murder of his mother became the final barrier separating Nero from his ultimate downfall. Nothing else restrained his wicked inclinations.

Shift in the state’s course

In the early 60s, Nero and his entourage became engulfed in endless feasts, completely losing their sense of shame and moderation. State affairs held little interest for the emperor; he wholeheartedly devoted himself to his beloved pastime—the theater, which was deemed unacceptable for the ruler of Rome and was previously considered disgraceful.

- I recommend reading about the theaters of Rome

Nero organized spectacles and shows, performing as a singer and circus artist before the courtiers, forcing everyone to participate in these performances. Interestingly, even the most distinguished Romans were compelled to play roles in the emperor’s shameless productions—some were coerced through threats, while others were bribed with lavish gifts.

Endless feasts and banquets required significant financial expenses, and soon the treasury began to experience a deficit. Gradually, the relatively sound state policy previously implemented by Seneca and Burr changed.

Nero no longer needed companions and mentors. Seneca was accused of embezzlement by his own student twice and withdrew from state affairs. The philosopher took his own life in 65 AD on Nero’s orders. The formal pretext was the accusation of Seneca’s involvement in the Piso Conspiracy.

Burr died even earlier, in 62 AD—researchers still debate whether his death was violent or if the statesman succumbed to illness. He was succeeded by Sophonius Tigellinus, whom contemporaries considered one of the most vile scoundrels of the time. This man came from humble origins and paved his way to power through the most dishonorable methods. Tigellinus became Nero’s closest companion in a series of endless feasts and other depraved and shameful indulgences. The emperor’s domestic policy finally acquired all the traits of tyranny:

- Processes of insulting majesty were constantly initiated, resulting in numerous executions.

- Confiscation of property from members of the aristocracy was carried out to attract funds to the depleted treasury due to these indulgences.

- Harsh repressions against political opponents were accompanied by an increase in informants.

- Pressure on the provinces intensified, causing sharp dissatisfaction among the populace. Taxes rose once again.

Persecution of Christians. Execution of Peter and Paul

Officially, the new religion, whose followers were mostly apostates and representatives of the lower classes, was not prohibited. Romans were free to believe in any god they desired, as long as their faith did not interfere with the worship of the emperor and reverence towards him.

In persecuting Christians, Nero was primarily driven by political, rather than religious, motives. It was necessary to find the culprits responsible for the devastating fire in Rome (in the year 64), and the emperor chose followers of the new religion for this role.

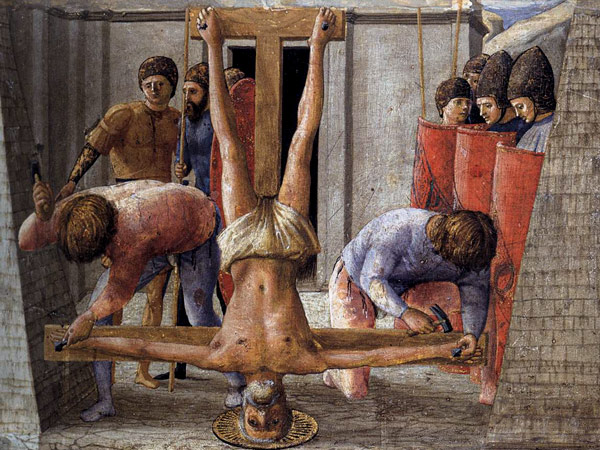

Among those destroyed by Nero were renowned apostles Peter and Paul, often referred to as the foremost. Peter and Paul are frequently depicted together in icons, although they arrived at Christianity through different paths. Peter was a fisherman and owned a boat but left his home to dedicate his life to serving God. His wife followed him, sharing in all the hardships of preaching.

The apostles, being eloquent preachers, convinced people that there was a power far more significant than the emperor. The devastating fire in Rome in the year 64 served as a sufficient pretext for the arrest of Peter and Paul.

Researchers still do not have a consensus on the exact date of the apostles’ demise. According to one version, it occurred in the year 67. Some scholars believe that the execution took place in 64.

Paul was a Roman citizen, which granted him the privilege of a more lenient execution—he was beheaded without undergoing torture. The relics of the apostle are preserved in Rome, in the Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls (Basilica di San Paolo fuori le Mura).

Both apostles were executed in the same place where they faced martyrdom, along with other Christians – in the famous Circus of Nero (“Circus Gai et Neronis”). This structure, originally built by Caligula, was located within the territory of modern-day Vatican City (Stato della Città del Vaticano) and was used for entertainment events, chariot races, and other spectacles.

- There is also a version that Peter was crucified on the Janiculum Hill (Gianicolo) at the site where the Bramante Tempietto stands today.

According to tradition, Peter was buried on the Vatican Hill (Mons Vaticanus). Several centuries later, the renowned St. Peter’s Basilica (Basilica di San Pietro) was built on this site – the primary Christian church in the world, occupying a central place in the Vatican and serving as a place of pilgrimage for countless people.

The Fire of Rome

Nero’s debauchery, his ill-conceived domestic policies, and endless repressions began to cause discontent among the nobility. The emperor was unpopular among the aristocrats who traditionally served as the pillar and support of imperial power in Rome. Fearing for their lives, the Roman elite outwardly expressed admiration for their reckless ruler, but among them, the number grew of those who dreamed of overthrowing Nero.

The culmination of the madness that engulfed the great Empire under its ruler’s whims can be considered the horrific fire in the summer of 64 AD. The flames engulfed the entire city and destroyed a large part of it. The inhabitants of the city were in a state of terrible turmoil, not knowing where to find salvation from the fire. Those who survived the fire were crushed by the mob – panic gripped Rome.

Within nine days, a significant portion of the houses of the Eternal City, magnificent temples, architectural monuments, and numerous other structures were destroyed.

Rumors circulated that the devastating fire was initiated by the mad emperor to rebuild a new city in his honor, named “Neronea.” However, historical evidence supporting this claim has not been found.

On the contrary, Nero attempted to take measures for the swift restoration of Rome. He distributed food to the destitute residents and ordered the construction of temporary shelters for the survivors. The newly laid streets in the charred remains showcased skilled architecture. The renovated city was adorned with sturdy stone houses, beautiful fountains, colonnades, and pools. Despite Nero’s efforts to alleviate the disaster’s aftermath for the common people, he failed to regain their former love and trust.

The situation worsened when Nero began constructing the opulent “Domus Aurea” (Golden House) on the site of the old imperial palace. The Golden House was unparalleled in its luxury, boasting intricate architecture and grand dimensions. Its central hall featured two vaults, one of which was set in motion by the efforts of slaves. Through openings in the dome, flower petals would shower down on the palace guests, accompanied by fragrant scents.

Nero’s personal life also took a dark turn. His once-beloved wife, Poppaea, grew weary of the emperor’s indulgence in extramarital affairs. In 63 AD, the empress gave birth to a daughter whom Nero adored. Unfortunately, the child passed away in infancy, not living to see her first birthday. After giving birth, Poppaea lost her former beauty, grew embittered, and was tormented by jealousy and fear of losing her amorous husband. Nero became burdened by her presence.

During Poppaea’s second pregnancy, in a fit of drunken quarrel, the emperor kicked her in the abdomen. The empress and her unborn child perished. This tragic event occurred in 65 AD.

Death of the Emperor

With each passing year, the behavior of the emperor became increasingly extravagant, and his antics astonished even the Romans who were not known for their strict morals.

Dissatisfied individuals, including Nero and his entourage, dealt with them in the most gruesome ways: they were sewn into animal skins and handed over to be torn apart by dogs or turned into living torches. A series of conspiracies arose against the emperor, none of which succeeded.

Sooner or later, Nero’s excesses in his indulgences, the weakness of internal and external policies, cruelty, and repression were destined to end in tragedy, which indeed occurred on June 9, 68 AD.

Initially, the provinces, ravaged by exorbitant taxes and led by governors, rose in rebellion, and then the residents of Rome began to express their dissatisfaction. When the unrest escalated into open revolt, the Senate supported it by condemning the infamous emperor. Even the once loyal Praetorians, who had been promised enormous monetary rewards, betrayed Nero.

Nero had to flee in simple attire, accompanied by a few slaves, to the villa of his freedman Phaon. There, he intended to end his life through suicide, but being spiritually weak, he struggled to make that decision. Only when armed centurions approached the villa did he, with the assistance of his advocate Epaphroditus, plunge a dagger into his throat.

On June 9, 68 AD, the fourteen-year reign of the last of the Julio-Claudian dynasty came to an end.

In the minds of most people, Nero embodies the worst traits a person can possess—a deranged tyrant and murderer. Indeed, the emperor’s actions are horrifying, yet it would be incorrect to give his personality a one-sided assessment.

Weak-willed, devoid of parental love, burdened with a flawed inheritance and fragile psyche, the young man ascended to the leadership of the mighty Roman Empire even before reaching adulthood. His own mother and other close individuals exploited him in their power struggles, disregarding his feelings and desires. All of this gave rise to a monster whose name is associated with the bloodiest atrocities in history.

Interesting Facts

- Emperor Nero, born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus in 37 AD, ascended to the throne at the age of 16, making him one of Rome’s youngest emperors in history.

- Nero had a passion for the arts and was an accomplished musician, singer, and charioteer. He even participated in public performances, often receiving favorable reviews from the Roman audience.

- In 64 AD, a devastating fire engulfed Rome, destroying a significant portion of the city. Nero was accused of starting the fire to make way for his grand architectural projects, but historical evidence supporting this claim is scarce.

- To divert blame for the fire, Nero targeted the Christians, initiating harsh persecution against them. Many Christians were arrested, tortured, and executed, leading to a wave of martyrdoms.

- Nero’s extravagant lifestyle was marked by lavish spending and opulent architectural projects. He constructed the Domus Aurea, a vast palace complex with lush gardens, artificial lakes, and even a colossal statue of himself, the Colossus of Nero.

- The emperor had a fascination with Greek culture and attempted to promote a fusion of Roman and Greek traditions. He participated in Greek-style games, including the Olympic Games, where he won several competitions.

- Nero had a tumultuous personal life, marrying and divorcing several times. His most famous wife was Poppaea Sabina, whom he married after divorcing his first wife, Octavia. However, he eventually killed Poppaea in a fit of rage.

- Despite his artistic pursuits, Nero’s rule was marked by tyranny and paranoia. He executed numerous senators and prominent individuals, including his own mother, Agrippina the Younger.

- In 68 AD, a rebellion led by Galba, governor of Hispania Tarraconensis, led to widespread dissatisfaction with Nero’s rule. Facing imminent arrest and execution, Nero committed suicide on June 9, 68 AD, bringing an end to his tumultuous reign.

- Nero’s death sparked a year of civil war known as the Year of the Four Emperors, as various generals and factions vied for control of the Roman Empire, further destabilizing the already volatile political climate.

Italy for me From Italy with love

Italy for me From Italy with love